Who Were the Patrons of Art in the Late 1900s and Where Was the Center of Modern Art?

Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai, c. 1446–51, Florence, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What'south in it for me?

Why would someone patronize art in the renaissance? Giovanni Rucellai, a major patron of art and architecture in fifteenth-century Florence, paid Leon Battista Alberti to construct the Palazzo Rucellai and the façade of Santa Maria Novella , both loftier – contour and extremely costly undertakings. In his personal memoir, he talks virtually his motivations for these and other commissions, noting that "All the to a higher place-mentioned things have given and requite me the greatest satisfaction and pleasure, considering in part they serve the honor of God besides as the award of the urban center and the commemoration of myself." [1]

Leon Battista Alberti, Façade of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, 1470 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 2.0)

Aside from bringing laurels to one's religion, city, and self, patronizing fine art was also fun. Earning and spending money felt good, specially the spending office. As Rucellai goes on, "I really recollect that information technology is even more pleasurable to spend than to earn…." [2]

The ancient Roman world (with which much of renaissance Europe was incessantly fascinated) as well provided motivation for patronage. The liberal expenditure on art and architecture by ancient Roman

Cocky-fashioning

Commissioning an artwork ofttimes meant giving detailed directions to the artist, even what to include in the work, and this helped patrons way their identities. While the identity of Bronzino's Florentine sitter in a Portrait of a Young Man is unknown, the artist shows him continuing confidently in the limerick's center, looking out at us while dressed in expensive blackness satin, slashed sleeves, and a codpiece consummate with golden aglets. He holds his fingers between the pages of a verse book, which rests atop a tabular array carved with grotesque faces. The book and the table were undoubtedly intended to convey the man's sophistication and learning while his clothing and upright posture showed his wealth and nobility.

Left: Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 10 lx cm (National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 2.0); correct: Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Carthusian, 1446 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The renaissance was also a time when increasingly wealthy center-course merchants and others aspired to increase their social recognition and began to commission portraits, as we see in double portraits similar January van Eyck'due south The Arnolfini Portrait showing the Italian merchant Giovanni de Nicolao di Arnolfini with his married woman in Bruges (in present-twenty-four hours Kingdom of belgium). Petrus Christus'south Portrait of a Carthusian reveals the increasing prominence of religious figures, with clergy, monks, and nuns sitting for portraits, many of which were likely fabricated to celebrate the entry of wealthy individuals into religious orders.

Ottavio Vannini, Michelangelo Presenting Lorenzo the Magnificent de' Medici with his Sculpture of a Faun, 17th century, fresco, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

Wealth, power, and status

In a seventeenth-century fresco by the creative person Ottavio Vannini, Michelangelo, the artist, is shown presenting the powerful Florentine, Lorenzo the Magnificent de' Medici, with a sculpture of a faun. Lorenzo sits at the centre of the prototype, facing frontally similar a ruler, while Michelangelo stands off to the side, bowing respectfully towards him. While today the proper noun Michelangelo is ameliorate known, in the fresco the Medici patron is shown as more than important than the artist.

Left: Leon Battista Alberti, Basilica of Sant'Andrea, 1472–xc, Mantua (Italy) (photograph: Steven Zucker, CC: By-NC-SA 3.0); right: El Escorial, begun 1563, near Madrid, Spain (photo: Turismo Madrid Consorcio Turístico, CC BY 2.0)

Paying for something lavish and monumental, such equally Sant'Andrea in Mantua (commissioned past Ludovico Gonzaga, ruler of the Italian metropolis-state of Mantua and built by Alberti) or El Escorial (commissioned by Philip II, Male monarch of Kingdom of spain, outside of Madrid), was a powerful statement well-nigh a patron's wealth and condition. Philip II was deeply involved in the planning of the massive complex that became El Escorial (a monastery, palace, and church). The complex was built in an austere, classicizing style that was intended to showcase Philip'due south imperial power by looking to ancient Roman architectural forms.

Left: Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, view in the chapel of the Hospital of Saint Anthony, Isenheim, c. 1510-15, oil on wood, 9′ 9 1/two″ x 10′ 9″ (closed) (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France); correct: January van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece (open), completed 1432, oil on wood, xi feet v inches x 15 anxiety 1 inch (open), Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium. Note: Just Judges panel on the lower left is a modern copy (photograph: Closer to Van Eyck)

Spiritual condolement and salvation

Some patrons paid for art to serve a larger purpose, perchance to fulfill a devotional or religious need, as the Isenheim Altarpiece did for people suffering from the painful disease of ergotism. Others commissioned fine art to expiate the patron'due south sins for such things every bit usury, every bit Jodocus Vijd desired when he paid a large sum of money for the Ghent Altarpiece .

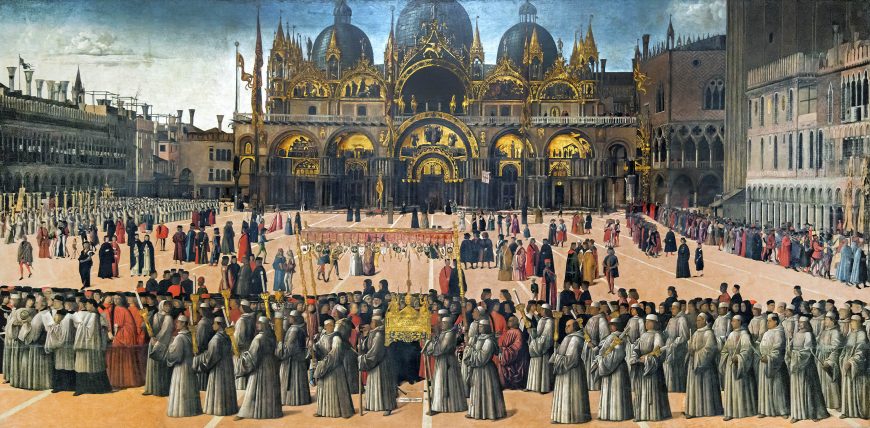

Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark's Square, 1496, tempera on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (photo: Steven Zucker, CC: Past-NC-SA iii.0; Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

Inspiring civic duty and responsibility

Commissioning artworks likewise helped to inspire civic responsibleness or to demonstrate that members of a item community performed their duties properly. The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista , 1 of many Venetian devotional confraternities, paid Gentile Bellini to describe the procession of the relic of the True Cross through St. Marker's square. This commission highlights the importance of the miraculous object besides as the civic duty of the city'due south citizens, who are shown in the painting'southward foreground, with the Scuola members conveying a canopy above the relic.

Patrons in fine art

Patrons often had themselves incorporated into paintings and sculptures to remind viewers of who had paid for the piece of work of fine art as well as to show themselves participating in the narrative. Nosotros call these "donor portraits." Lluis Dalmau's Virgin of the Councillors , for instance, shows the Virgin Mary enthroned, belongings the baby Jesus and surrounded by saints in a luxurious Gothic interior. Kneeling earlier the saints, at the edge of the throne, are five men, all of whom were members of the Barcelona Urban center Council (Casa de la Ciutat), who had paid Dalmau to create the painting to hang in the chapel at the council palace. The portrait collapses sacred and secular time, placing the men as perpetually revering Mary and showcasing their piety to anyone observing the painting.

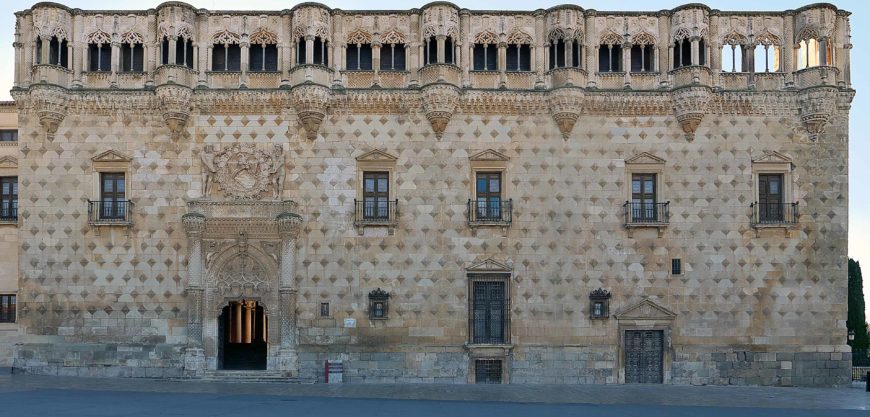

Juan Guas, Palacio del Infantado, 1480, Guadalajara, Spain (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 3.0). The patron was Íñigo López de Mendoza y Luna.

Fifty-fifty in instances where patrons were not overtly depicted in artworks, artists would sometimes exist directed to include heraldic symbols, visual puns, or other motifs to allude to the patron. The glaze of arms of the wealthy Mendoza family rests above main entrance to the Palacio del Infantado (in Guadalajara, Kingdom of spain) amidst the decorative plateresque elements, and advertizing to whatsoever passersby who had paid for and lived in the striking palace.

The Tomb of Juan II of Castile and Isabel of Portugal in front of the altar of the church of the Carthusian Monastery of Miraflores (photograph: Ecelan, CC BY-SA iv.0)

Patrons equally influencers

Patrons also set fashions for style and discipline matter. Importing artists and artworks from distant lands could testify off 1's sophistication and introduce new styles, techniques, and subjects to local audiences. Artists and fine art traveled widely during this period, and exchanges beyond Europe and across were common. Because of the wealth and glamour of northern European court culture, information technology was fashionable for the wealthy elite of Italy and Kingdom of spain to import both Netherlandish fine art and artists. Queen Isabel of Castile, whose begetter had favored Flemish painters such as Rogier van der Weyden, had a number of artists, including Juan de Flandes, Michel Sittow, and Gil de Siloe, at her court to create lavish works that would speak to her ability and magnificence.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, 1476 and 1470, oil on console, 253 cm x 586 cm (Uffizi Gallery)

Likewise, Tomasso Portinari, who worked for the Medici bank in Bruges, hired the northern artist Hugo van der Goes to paint a massive altarpiece of the Nascency for his habitation boondocks of Florence, Italy. When put on display in the hospital church of Santa Maria Nuova in 1483, it created a sensation. Italian artists, in awe of the accomplishments of the northern primary, speedily responded to what they saw. Portinari non but showcased his own cosmopolitan sophistication, he also helped shape the direction of Florentine art by introducing this spectacular image to local artists.

Why patrons affair

Fine art communicated ideas about patrons. Status, wealth, social, and religious identities all played out beyond paintings, prints, sculptures, and buildings. At the same fourth dimension, the careers of artists were shaped with the help of powerful patrons. Too, artistic styles emerged or developed as a effect of patrons hiring artists or buying artworks and past transporting them to new locations. The history of fine art has been shaped not but by artists, but as well by the patrons whose choices in sponsorship determined what fine art was created, who created it, who saw information technology, and what art was made of. Until the modernistic era, the stories that have been told in art are the stories that reflect the interests of the rich and powerful, the privileged few—by and large men—who were in positions to patronize art. In a nutshell, patronage mattered.

Notes:

[ane] Giovanni Rucellai, Giovanni Rucellai ed il suo Zibaldone , ed. Alessandro Perosa. 2 vols. (London: The Warburg Constitute, Academy of London, 1960), one:121

[2] Rucellai, Zibaldone , 1:121

Additional resource

Read more well-nigh Isabella d'Este and her patronage

Acquire more almost patronage in fifteenth-century Burgundy

Explore renaissance Spain further, and learn more than about the patronage of Queen Isabel of Castile

Learn more about Patrons and Artists in Late 15th-Century Florence from the National Gallery of Fine art

Read virtually patronage at the later Valois court on the Heilbrunn Timeline

Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless 1364–1419 ( Dijon, 2004)

Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Mode , 2d ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

Rafael Domínguez Casas, "The Artistic Patronage of Isabel the Cosmic: Medieval or Modern?," in Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona , edited by Barbara F. Weissberger (Boydell & Brewer, 2008), pp. 123–48

Alison Cole, Virtue and Magnificence: Art of the Italian Renaissance Courts (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1995)

Tracy E. Cooper, " Mecenatismo or Clientelismo ? The Graphic symbol of Renaissance Patronage," in The Search for a Patron in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance , edited past David G. Wilkins and Rebecca L. Wilkins (Medieval and Renaissance Studies 12. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1996), pp. xix–32

Mary Hollingsworth, Patronage in Renaissance Italia: From 1400 to the Early Sixteenth Century (London: Thistle, 2014)

Robrecht Janssen, Jan van der Stock, and Daan van Heesch, Netherlandish Art and Luxury Goods in Renaissance Spain: Studies in Laurels of Professor Jan Karel Steppe (1918–2009) (Belgium: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2018)

Dale Kent , Cosimo De' Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron's Oeuvre (New Haven: Yale UP, 2000)

Catherine E. King and Margaret 50 King, Renaissance Women Patrons: Wives and Widows in Italia, C. 1300–1550 (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1998)

Sherry C. M. Lindquist, Agency, Visuality and Lodge and the Charterhouse of Champmol (Aldershot and Burlington, 2008)

Michelle O'Malley, The Business concern of Art: Contracts and the Commissioning Process in Renaissance Italia (New Haven: Yale Upwardly, 2005)

Sheryl Reiss, "A Taxonomy of Art Patronage in Renaissance Italy," in A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art , ed. Babette Bohn and James G. Saslow (Chichester, Westward Sussex U.k.: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), pp. 23–43

Hugo Van der Velden, The Donor'due south Image: Gerard Loyet and the votive portraits of Charles the Bold (Turnhout, 2000)

Jessica Weiss, "Juan de Flandes and His Fiscal Success in Castile," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 11:1 (Wintertime 2019) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2019.11.ane.2

Cite this folio as: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Heather Graham, "Why commission artwork during the renaissance?," in Smarthistory, April 24, 2020, accessed Apr 25, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/renaissance-patrons/.

brooksdaithis1997.blogspot.com

Source: https://smarthistory.org/renaissance-patrons/

Post a Comment for "Who Were the Patrons of Art in the Late 1900s and Where Was the Center of Modern Art?"